Commentary

Erica Russell and Ian Christie

25 October 2023

How climate change strategy fits into the UK’s governance systems might seem a technical and tedious question to consider, in the face of the urgency of cutting emissions and adapting to global heating. But governance – the web of relationships between the national and local public authorities, other sectors and the citizen in devising and implementing policy – matters hugely.

Who is in charge, and what’s the division of labour in the complex task of remaking our economy and institutions for net zero transitions? In the wake of the UK Government’s recent shifts in its net zero strategy, the governance of our climate policy is the subject of heated, even angry, fresh debate.

Much work has been undertaken at large-city scale to both understand and organise effective climate governance, with networks such as C40 Cities continuing to develop and exchange best practice. But of course there is a world of local governance and policymaking beyond major urban centres. In 2020 in England, just over 19 million people lived in predominantly rural places, or urban authorities with significant rural areas, with a further 14.2 million people living in small cities and towns. Most English citizens live within county or unitary local authority areas.

In these rural and semi-urban areas climate governance is being led and developed by multiple elected councils, diverse stakeholders and complex partnerships. And all of them must operate across a rich variety of geographies, as well as across multiple scales of policy and governance.

How is climate policy governed in this complex set of local environments? In our new report for the Place-based Climate Action Network, we explore this under-considered issue by focusing on one UK county and local governance area: Surrey. This provides a valuable case study of multi-level governance in an area of relative affluence and where the county council and partners are increasingly focused on climate action. The research reveals a lot of pioneering and highly motivated work across levels and sectors – but also huge frustration at the barriers to effective and joined-up local action and leadership on climate, with messages for the UK Government and the whole English system of local governance.

Insights from Surrey's climate community

In 2020-22 we carried out over 40 interviews with policymakers at all levels of governance in the county, from parishes to regional bodies, with other local stakeholders, and with some climate policy experts at national level; and we mapped the climate policy structures and networks in the county. Our findings reinforce the widespread perception of a serious disconnection between climate strategy and place-based governance. As many others have reported – most recently Chris Skidmore MP in his Mission Zero reports – a reluctance by central government to set out a framework of roles and responsibilities for local authorities has meant that councils and their partners are operating in conditions of uncertainty and lack of clear direction.

We also found evidence of these problems at the ‘micro-local’ governance levels too, in parish and town council networks. Just as sub-regional local authorities can struggle to obtain funds, strategic direction and information from government, actors at borough and parish levels feel they are not getting the support they need from county and other sub-regional bodies. We found local organisations expressing frustration as they struggled to understand the institutional division of labour in climate policy and action, not just across the county, but increasingly also at regional scale.

What kind of a local ‘climate mandate’ for action do we need? The issues and options are contested within local government as well as between national government and local actors. Four major strands of debate and advocacy emerge from our fieldwork in Surrey and research elsewhere. Interviewees offered variations on all the following positions concerning the ‘mandate’ for climate action at local level:

- Sub-national bodies need statutory net zero powers to underpin and boost local mandate and capacity to pursue net zero.

- Statutory powers are needed to fill gaps not covered by voluntary or existing powers.

- Local mandates for action have been established already through climate emergency declarations by councils and through other local responses to the national net zero strategy and the rise of climate concern among citizens; what is missing is the capacity for effective action.

- Sub-national bodies already have the powers and legitimacy needed to pursue policies for net zero emissions, but lack the resources and strategic direction from the national level to make the most of these.

Underlying all these positions, there was a strong sense from all of our respondents that multi-level climate governance in the UK is broken, or at best only partial and incoherent. The view also came through that central government is focused on national-scale policy on climate, and with a technologically driven view of what changes are needed. National policy has so far neglected the need for civic engagement and lifestyle change, and above all has failed to recognise the vital role to be played by local government and its partners.

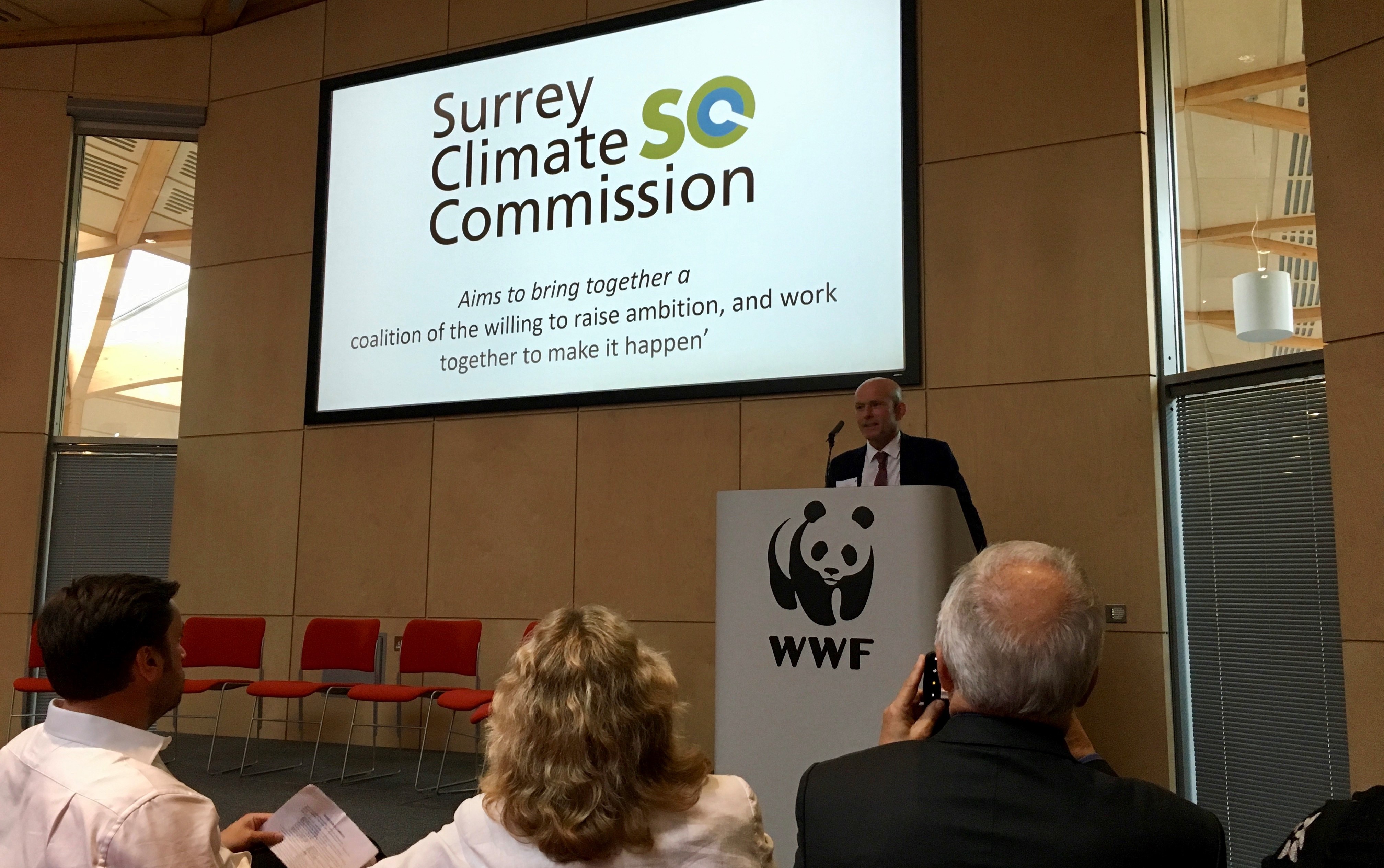

How have local actors responded to this state of affairs? Based on our review of the literature and on our fieldwork in Surrey, we found a new form of local governance, that of Improvisatory and Compensatory governance, emerging. In this form of governance, local councils and their partners – such as the Surrey Climate Commission, a voluntary organisation set up in 2019 – make progress piecemeal, attempting to make the most of limited powers and using their convening capacity. This opportunistic and piecemeal approach is ‘compensating’ for the lack of coherent multi-level guidance and division of labour on climate action, and inevitably is sub-optimal.

Many place-based approaches were being invented in Surrey and tested in this spirit of improvisation and compensation in the absence of a clear national-local framework. This has given rise at a local level to governance that is “really wavy and sort of moving” , as one interviewee said. For some actors, this offers the potential for truly local interventions, allowing a more holistic place-based approach, but for others there is a sense of wasted time and lack of direction.

There was a wide and strong consensus on the barriers to effective multi-level governance of climate policy. These were seen as:

- A lack of recognition from central Government on the role of local government in climate action;

- The lack of mechanisms and political will for strategic partnership with local government and its stakeholders;

- The emphasis in net zero policy on top-down ‘techno-centric’ strategy and processes;

- The piecemeal and short-term nature of funding available to local government.

This set of findings from expert respondents across Surrey reflects and reinforces the results from the Skidmore Review of Net Zero and many other recent reports. Outside central government, the consensus on the dysfunction in UK climate policy is rock-solid.

‘Alphabet soup poured over a spaghetti junction’

Yet, whilst there is consensus about the issues, there is as yet no clear vision for effective governance of climate policy across multiple scales. Many working at local and micro-local level felt their work was ‘invisible’ to those at higher governance positions, and knowledge of county or even district level action was rarely understood without the intervention of ‘boundary-spanning’ individuals or projects. In the absence of a clear and formalised framework for climate governance linking national to local scales, successful action was frequently identified as the work of ‘wilful actors’ or passionate individuals rather than a direct result of embedded governance structures. This gives rise to risks of transience of impact and lack of continuity, as roles change, and initiatives lapse.

Regional climate bodies - such as the government-funded Net Zero Energy Hubs - have offered positive support, but the potential short-term nature of such bodies (as seen with the demise of Local Enterprise Partnerships), and their lack of connection to local democracy, make long-term policymaking and implementation more difficult. Such bodies also add further complexity to governance structures, with non-standardised overlapping scales of place-based delivery. The complaint was clear, that the English governance map is an alphabet soup poured over a spaghetti junction of linkages. Clarity is urgently needed to help make progress with net zero, which affects every level, area and sector.

Making multi-level governance work for net zero

Our new report offers recommendations, based on our findings and the wider recent policy literature, for UK climate policy, the development of new governance models and also for climate action in Surrey. For reform at national level, we back the recommendations of the Skidmore Review, which chime with the views from our respondents in Surrey. Local government needs clarity from the centre about the climate policy division of labour, the resources to implement net zero policies and report on progress, and reform in the planning system to ensure that new developments help deliver emission reductions and other gains for climate policy and local wellbeing. Local government needs a duty to pursue net zero across policy areas and to report on progress – and it needs the resources and revenue-raising powers to be able to deliver results.

For further progress in Surrey, regardless of what happens at national level, we recommend that Surrey County Council support the development of a ‘mesh’ (Mulgan, 2020) of vertical and horizontal relationships and governance arrangements for the county, with an aim to develop a local ‘climate constitution’, a map of roles, responsibilities, reporting and resources. This would include parish and town councils, which have great potential to be important actors in connecting neighbourhoods and citizen-led projects to wider climate strategy at county and district/borough levels.

Surrey should aim to become an exemplar of local climate governance in public communication, capacity- and confidence-building at community level via parish and town councils, and debating and reporting of challenges and progress. To that end we recommend that the County Council and its partners hold an annual local climate assembly, and we would suggest that in delivering climate action, actors within the county must consider the effectiveness of scale, perhaps as part of boundary-spanning projects. If we want successful climate action in Surrey, we must build in flexibility of delivery into a county-wide climate framework and harness the strengths of the county’s rural base.

There is a powerful consensus that local governance is crucial to the net zero transitions we need. There is an equally strong consensus that local councils and their partners are being held back by dysfunctional governance – a lack of coherence in national strategy and planning system, and lack of resources and clear roles for local actors. Our study of Surrey reinforces this analysis, and points to ways ahead for national policy and for local actors alike.

Read the authors’ new report ‘On multi-level climate governance in an urban/rural county: A case study of Surrey’ published by the Place-based Climate Action Network on 25 October 2023.

Policy briefings have also been produced on:

- The importance of People Based Climate Networks in sub-national net zero action

- The unacknowledged role of micro-level governance in net zero action

- Multi-levels of information, tools, data and other resources

Dr Erica Russell is a sustainable development consultant and a visiting research fellow at the Centre for Environment and Sustainability (CES) at the University of Surrey. Ian Christie is an associate professor in CES and a fellow of the University of Surrey’s new Institute for Sustainability.